The invisible zone - between gaze and self-image

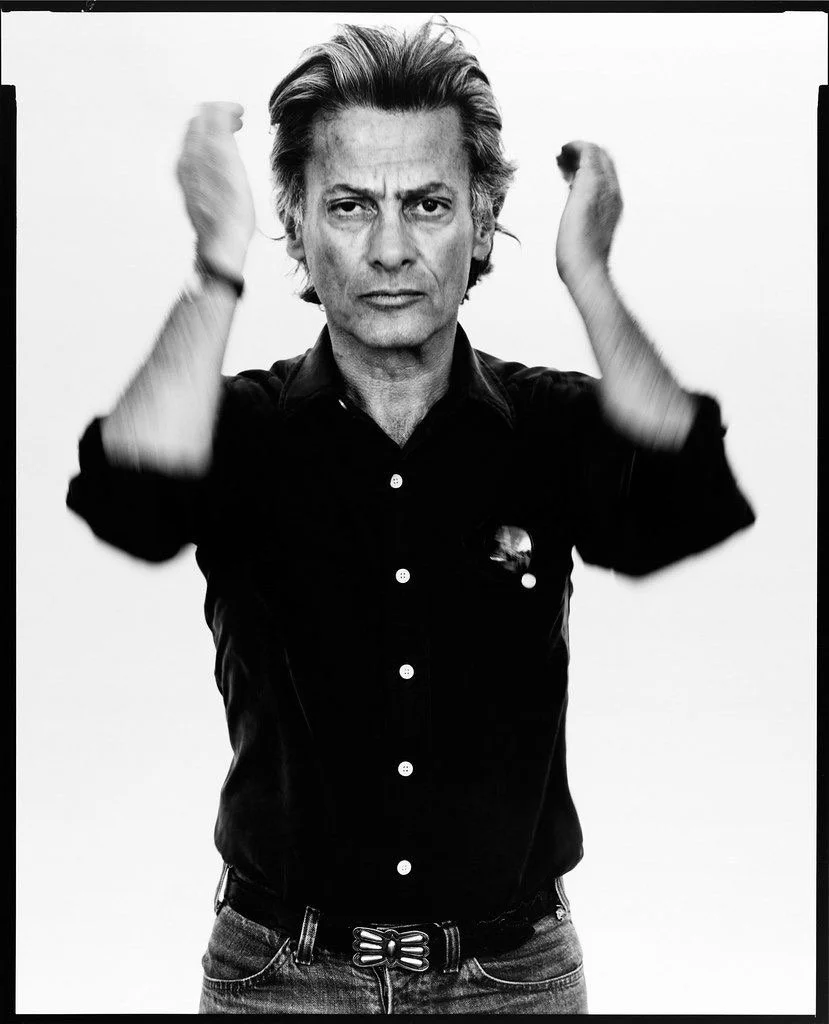

There is this self-portrait by Richard Avedon.

He stands frontally in front of the camera, like many of the people he photographed. White background - his classic. Black shirt, hair a little too long, only roughly in shape. The picture could have been taken just last year.

His arms are in motion. Probably not planned. The resulting blur makes the picture even more exciting. Our gaze is automatically drawn to his face. Sharp, concentrated, alert. As if he wanted to make something clear at this very moment. Like only he can do it like this right now.

I was not primarily fascinated by this photo because it is so strong. It occupied me because I asked myself: Why is he taking a self-portrait? What can he show with it that no one else could capture for him?

Richard Avedon

I'm also thinking of Annie Leibovitz photographing herself in the bathroom mirror of a hotel room in San Francisco in 1970. Why?

To Vivian Maier, who appears as a shadow, reflection or fleeting silhouette in her own pictures. Why?

To Claude Cahun, Francesca Woodman, Zanele Muholi. How they all portrayed themselves at some point. Why?

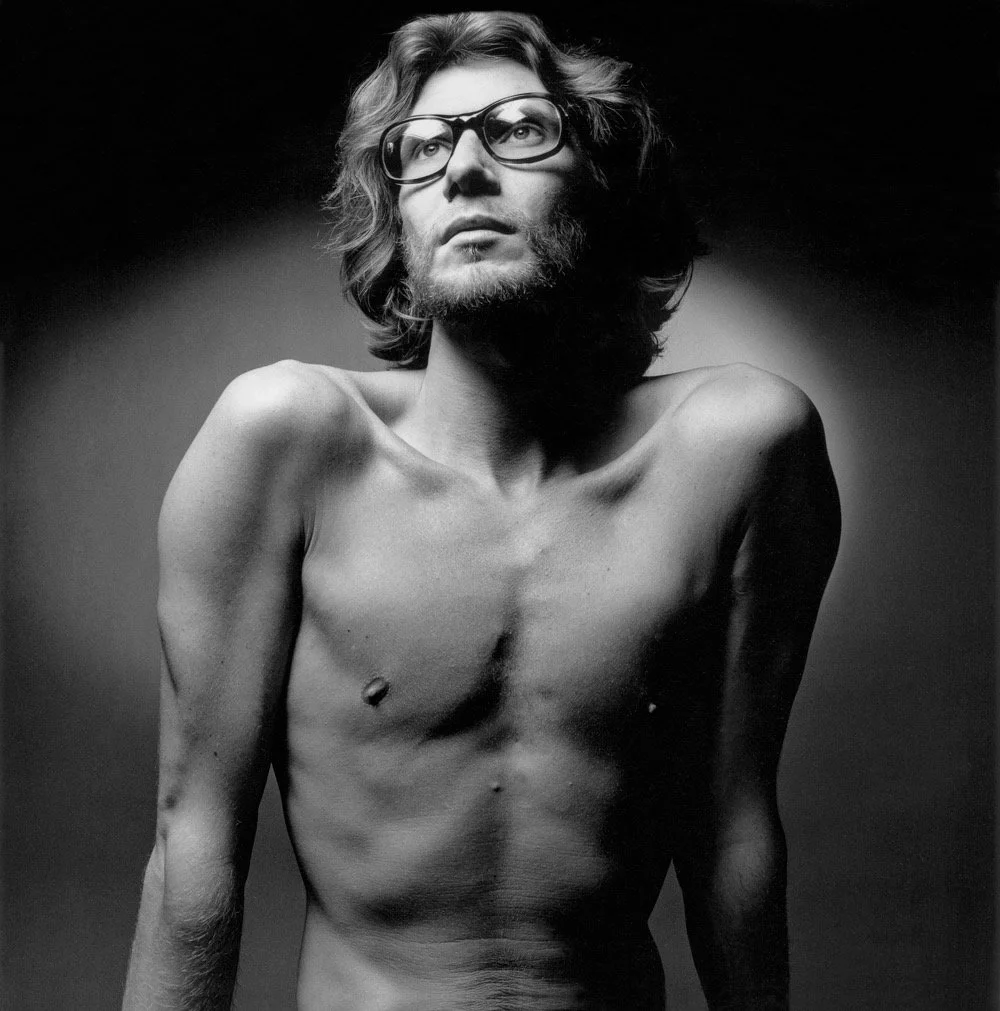

And to Yves Saint Laurent - photographed by Jeanloup Sieff. This famous nude photo from a series.

For many years, I actually thought it was a self-portrait.

That's how much it radiates this controlled, deliberate look. As if he himself had decided how he wanted to be seen - and pressed the remote shutter release.

That's what really got to me: that a picture, even if it's not of the person being photographed, can look like a self-portrait.

Because photographer and subject enter the same space in that brief moment - that neutral zone where their gaze falls on the person being photographed and overlaps.

Yves Saint Laurent - photographed by Jeanloup Sieff

On a long car ride, a thought came to me that was just there - like a kind of discovery where scientists stumble upon something through serendipity.

I was thinking about self-portraits and suddenly realized: there's a zone where what I see of someone and what that person wants to show of themselves overlap.

How big is this area?

And is it a good thing if it is big?

There are self-portraits that say: "Let me do this. Only I can show myself as I am - or as I want to be seen."

Others hide. They turn their face away, leave the camera in between, perhaps show a pose that they would never show recognizably with their face.

I'm not talking about selfies or snapshots here. I'm talking about the world of photography, where a self-portrait is more than just a photo of yourself.

There is something magical when people portray themselves.

And perhaps - because I am so fascinated by this - this element flows unconsciously into my own photography. Maybe that's what makes a picture particularly intense: when something of this overlap is revealed at the moment of taking the picture.

The zone between gaze and self-image

In portrait photography, there is an area where two perspectives overlap: the photographer's gaze and the self-image of the person portrayed. A neutral zone that does not appear staged and yet is not created by chance. It cannot be forced. Rather, the working method is set up in such a way that it can emerge - through space for development, through openness, through allowing moments that were not planned. Technology takes a back seat. The relationship and the connection is the element that counts.

The need for a perfect surface is avoided. Skin retains its texture, shadows can be hard or soft, the surroundings can leave traces on the picture and play a part. Any smoothing that is too orderly removes the image from this overlap in which both perspectives meet.

The result is a portrait that belongs neither entirely to the photographer nor entirely to the person portrayed. It lies exactly in between - and perhaps it is this "in-between" that gives a picture a special intensity.

Many photographers, inspired by great fashion and portrait shots, use black and white as a synonym for authenticity. However, this often results in a rupture: staged scenes, combined with digitally smoothed skin and bright eyes, distance themselves from the direct encounter that constitutes true authenticity.

Self-portrait and trust

A self-portrait has its own magic: it is a moment in which the portrayer alone decides how to show or hide themselves. Everything - perspective, expression, timing - is in their own hands.

And yet there are portraits that, although taken by someone else, have the same power as a self-portrait. The photographs of Yves Saint Laurent, taken by Jeanloup Sieff, are an example. At first glance, you could be forgiven for thinking that Saint Laurent had staged himself. His presence in the picture is so direct, so natural.

Such shots are created when the person portrayed leaves something to the photographer that is normally only possible in self-dramatization - and the photographer does not disturb this trust, but preserves it. At such moments, the two perspectives merge and the image bears traces of both: the self-determination of the person portrayed and the openness of the photographer.

The connecting element

The special effect of a picture is often created in this invisible area in between. It is a space in which control and letting go, closeness and distance, self-image and external view find a balance.

And perhaps it is precisely this fragile balance that decides whether a picture is merely a depiction - or has a long-lasting effect - is unique.

The special effect of a portrait does not come from perfect lighting, not from the choice of lens and certainly not from a "look" that can be applied to every picture. It is created in that invisible area between photographer and subject - where two emotions touch without merging. (Sorry for so much meta level)

In this zone, each image carries something unique, something that cannot be copied. It is the opposite of images that appear to have been chased through a camera - perfect, smooth, interchangeable. Images that any better app will be able to produce tomorrow because they lack what can only be created in this encounter: an imprint of trust, timing and a genuine presence in the moment.

Perhaps that is the secret ingredient. It makes the difference between a picture that you look at - and a picture that looks at you.